Codex of the month (X-XI): Visigothic script manuscripts at the British Library

This month’s ‘Codex of the month‘ is not one codex nor two, but 16!! the full collection of Visigothic script manuscripts at the British Library.

As part of my ViGOTHIC research project [more here and here], in the next months, I will be working with some of the precious codices kept at the British Library – Additional ms. 30848, 30850, and 30851, besides Additional ms. 11695, the so-called Silos Apocalypse –, and so I thought that it would be nice to take a look at the other codices also copied in Visigothic script here in London.

reference > [date] > centre > content

1 Add. ms. 33610 > early 9th c. > unknown > Liber Iudicum (1 fol.)

2 Add. ms. 30852 > 9th c. > Silos > Liber Orationum (115 fols.)

3 Add. ms. 30854 > 9th c. > unknown > Gregorius Magnus, Liber dialogorum (182 fols.)

4 Egerton 1934 > early 10th c. > unknown > Chronicon (2 fol.)

5 Add. ms. 25600 > 10th c. > Cardeña > Passionarium Hispanicum (269 fols.)

6 Add. ms. 30846 > 10th c. > Silos > Breviarium Toletanum (173 fols.)

7 Add. ms. 30853 > late 10th c. > Silos > Homiliarium, Poenitentiale ecclesiasticum (324 fols.)

8 Add. ms. 30055 > late 10th c. > Cardeña > Codex Regularum (237 fols.)

9 Add. ms. 30844 > early 11th c. > Silos / Cardeña > Officia Toletana (177 fols.)

10 Add. ms. 30845 > 11th c. > La Rioja / Silos / Cardeña > Officia Toletana (161 fols.)

11 Add. ms. 30851 > 11th c. > Silos > Psalterium (202 fols.)

12 Add. ms. 30855 > 11th c. > Silos > Vitae Patrum (142 fols.)

13 Add. ms. 30847 > late 11th c. > Silos > Breviarium (188 fols.)

14 Add. ms. 30848 > late 11th c. > Silos > Breviarium (279 fols.)

15 Add. ms. 30850 > late 11th c. > Silos > Antiphonarium romanum (241 fols.)

16 Add. ms. 11695 > 1091-1109 > Silos > Beatus, In Apocalypsin (279 fols.)

The results of my first approach to discover this collection were presented as an informal talk at the London Graduate Paleography Group at King’s College London. Thanks for reading!

Discovering the collection of Visigothic script codices at the British Library

How to introduce something that should not require an introduction? It was in the year 1878 when the, back then, British Museum acquired a collection of 14 manuscripts and incunabula from the Spanish Benedictine monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos. The addition of these codices to the already well-populated treasuries of the Museum completed an extraordinary impressive corpus of medieval manuscripts written in the Iberian Peninsular most original script, Visigothic. In this post we will revise how these codices now at the British Library came to form the collection, highlighting its importance for studying the historical and cultural development of Iberia throughout the Middle Ages.

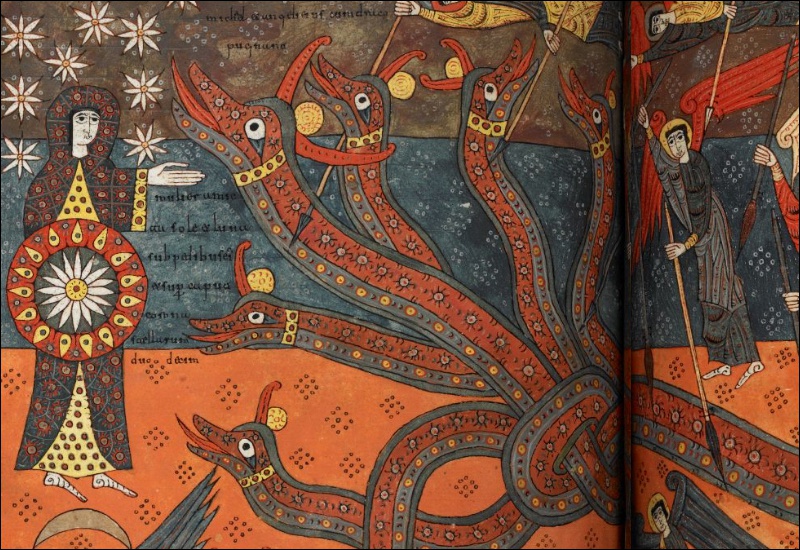

The Silos Apocalypse | © London, British Library, Add. MS 11695

The Silos Apocalypse | © London, British Library, Add. MS 11695

In 1840 which is now the gem of the Visigothic script collection of codices of the British Library and one of the most significant medieval manuscripts of the institution, entered the British Museum: Additional ms. 11695, the so-called Silos Apocalypse. The Museum bought it from José Bonaparte, who, while king of Spain from 1808 to 1813, added it to his personal collection. Additional ms. 11695 is one of the 32 codices of its type preserved, widely known as “Beatos”, which were copied from the late 8th to the 14th centuries. The Silos Apocalypse was finished in the scriptorium of Silos (Burgos) in the early 12th century; its text on 18 April 1091, its illumination programme on 30 June 1109, as their copyists inform us. It belongs to one of the most authentic manuscript traditions of the medieval Iberian Peninsula; it transmits a thorough, passionate, and lavishly illuminated commentary on the Apocalypse of St John of Patmos as well as other texts like the treatise De adfinitatibus et gradibus (a chapter from St Isidore’s Etymologies) and the commentary on Daniel by Jerome, that were commonly added to these volumes from the 10th century on. The Silos Apocalypse is an exceptional resource for art historians, but also to palaeographers since it is one of the only 49 codices of the almost 400 preserved written in Visigothic script that can be dated and placed with certainty and thus contextualised. As such, it is the focus of my current project ViGOTHIC about which you can read more here.

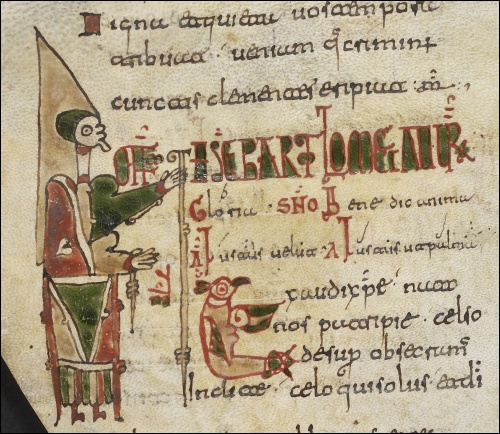

© London, British Library, Egerton ms. 1934

© London, British Library, Egerton ms. 1934

Merely 20 years after, in 1861, another unique piece arrive at the Museum. Within the binding of a mid-18th-century codex donated by the Egerton family, two folios of the Spanish Chronicle of 754. Currently under the shelfmark Egerton ms. 1934, these folios pair with four folios more now kept at Madrid (Real Academia de la Historia, ms. 81), and together constitute the earliest surviving copy of that chronicle since the only other two extant copies date from the 13th and 14th centuries. This Mozarabic Chronicle is supposed to have been compiled by an anonymous Mozarab living in a small city in south-east Iberia as a continuation of the Historia Gothorum by Isidoro de Sevilla. It covers the years from 610 to 754, and although it is focused mostly on Byzantine and Umayyad affairs, it is still an excellent historical source to dig in the first years of post-Visigothic Iberia.

The British Museum continued the acquisition of Spanish manuscripts by adding to its collection, in 1864, the manuscript identified as Additional ms. 25600, which must have been in private hands after the dissolution of monasteries in Spain in 1835. This codex was written in the monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña by the mid-10th century and compiles passions of the most important Hispanic saints venerated by that time.

Another manuscript from the same provenance and copied around the same time arrived soon after at the Museum, being bought from Sotheby’s in 1876: Additional ms. 30055. It contains a collection of rules (Liber regularum; Leander, Isidorus, Fructuosus, Smaragdus) for monastic use, an essential book for the spiritual wellbeing of monks and the functional organisation of the community.

By the time there were, thus, already outstanding exemplars of Visigothic script codices at the British Museum the collection received considerable additions. Indeed, in 1878 the institution acquired an almost complete set of medieval manuscripts written in Visigothic script supposedly in the same monastery, Silos, or its dependencies. In 1835, because of the dissolution of monasteries, the abbot of Silos tried to preserve the cenobium’s rare collection of codices by taking them with him when he took refuge in an abbey dependency of Silos in Madrid. However, when he died, his successors, concerned about reconstructing Silos, saw in the books a source of income. Sixty-nine manuscripts and incunabula were sold to a Madrid bookseller, later on, bought by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and by the British Museum. The later acquired fourteen, now Additional mss. 30844 to 30857; all of them except for Add. mss. 30849, 30856, and 30857, examples of Visigothic script. Some highlights of this collection:

© London, British Library, Add. MS 30845

Add. mss. 30844, 30845 and 30846, containing a collection of monastic officia texts of the Mozarabic Liturgy, and Add. mss. 30847, 30848 and 30849, their equivalent for the Roman Liturgy, are a primary source to study how the transition from the Mozarabic to the Roman rite developed in the mid-late 11th century in the Iberian Peninsula. Although not the only extant exemplars to carry out such study, these are the best-preserved ones.

Add. Ms 30850 is an exceptional Antiphonary for monastic use from the Roman tradition, preserved in its entirety. The notation it contains is Visigothic, even though the repertoire is Gregorian. In the upper and lower margins of some of its leaves, there are numerous annotations in Aquitanian notation which are considered to be among the first examples of this type written in the Peninsula.

Add. ms. 30851, which contains Psalms, hymns and canticles for the Mozarabic liturgy, to which a selection of Liber horarum was added, and that has been described as the best example of Silense script – of the script used in the scriptorium of the monastery of Silos by the late 11th century. The small marks you see all over the text, they are glosses, and this manuscript is representative for the use of neumes as reference signs to these glosses added in the margins. It was, it seems, a common practice in many of the codices from Silos, although the others are lacking the precision of this one. The glosses are mostly synonyms in the Vulgate, but in many other cases, they consist of lexicographical or contextual commentaries. They provide equivalent in Latin, although there are some words in the Romance vernacular too.

Add. ms. 30853 contains a collection of homilies and of penitential canons concerning the penances to be done for various sins. It is dated, by the palaeographic characteristics of the different hands which intervened in its copy, as an example of the second half of the 10th century. It has also been supposed to be copied in Silos. The relevance of this manuscript resides in the glosses, called ‘Glosas Silenses’, which a late 11th-century reader added in vernacular.

Add. ms. 30854, a Liber Dialogorum by Saint Gregory the Great, a collection of four books relating the life and miracles done by several holy men, mostly monastic, of 6th-century Italy, with the second book entirely devoted to Saint Benedict. This codex is the earliest of the only two extant exemplars of this work in Visigothic script. It has not been determined where or when it was written. No palaeographical study has been done. Bearing in mind the characteristics of the script, in my point of view, it could be attributed to a Castilian, and very prominent, production centre, copied in the early 10th century.

All these codices together, plus a fragment of an early 9th-century Liber Iudicum discovered at the British Museum soon after, now Add. ms. 33610 H, make up the collection of sixteen codices, whole books or fragments, in Visigothic script now at the British Library. Their chronology ranging from the early 9th century to the early 12th. Their topics common for medieval Iberian Peninsula but diverse: about law, a chronicle, and, of course, liturgical books for the daily Office and the celebration of the Mass and spiritual books for the transcendent and cultural training of the readers. They constitute an exceptional resource from which to study medieval written culture, and, from a non-scholarly perspective, beautiful books to look at.

by A. Castro

[edited 13/07/2018]

Michael Sibly

I would simply like to thank you for this wonderful website and set of resources. I am not a specialist in this field at all, and came across your work when investigating the early medieval kingdom of Asturias, and the late 8th century adoptionist controversy involving Bishop Felix of Urgell etc. I have visited different parts of northern Spain quite a few times in recent years, am familiar with many of the monasteries in the region, and in 2018 I walked the Camino Frances from Saint-Jean Pied de Port to Compostela. So I would just like to send thanks and very best wishes. Viva Europa!