The Medieval Chi-Rho in northwestern Spain

Have you found out what is that very strange thing at the beginning of Visigothic script charters? It‘s a Chi-Rho!

I have been struggling lately – editing and looking for ideas, thinking about the reviewer’s suggestions, etc. – around an article that has been accepted for publication in Scriptorium (yay!). Its provisional title, more or less, is ‘Observations on the Chrismon in the Visigothic script documents from the diocese of Lugo (917-1196)’ although after yesterday’s work I am maybe changing it to ‘Observations about the Chi-Rho used in medieval charters of northwestern Spain (10th-12th c.)’ [1]. As some of you may know, I have been working on Christian monograms for some time now. I have even presented the first draft of accomplishments earlier this year in Saint Louis at the 1st Annual Symposium on Medieval and Renaissance Studies [check the 2nd one for 2014]. So, why am I thinking of changing the title? Because, studying the meaning of this sign, I realised that its cultural implications are in fact even more important than I thought!

We know as Chi-Rho the Early Christian monogram formed by combining the Greek letters χ and ρ symbolizing Christ’s name (Χριστός), widely used in all types of media from antiquity to the present day. Saying that you are maybe thinking on some of the many examples that show up in Insular gospel books, like the Chi-Rho of the Book of Kells (above), the Book of Durrow or the one in the Lindisfarne Gospels.

What you may not know is how this sign is and how was it used in charters. How was it understood and developed by the northwestern Iberian peninsula scribes?

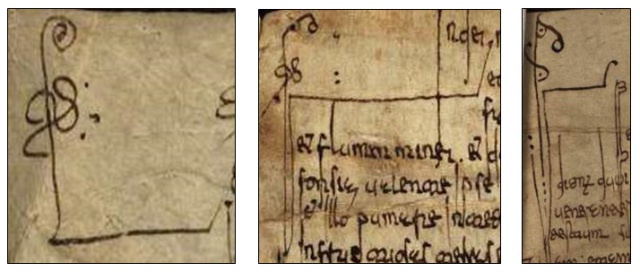

Within the diplomatic structure, the Chi-Rho was used in the initial part of texts, regardless of the type of document issued – private, royal or ecclesiastical –, preceding the verbal invocation, and also in the signature box where the subscriptions of witnesses confirming the documentary action were grouped, before each individual or group of individuals. Similarly, the sign can be found before the name of the scribe, when he is named on the charter. Let me introduce you to the ‘craziness’ of ‘my’ Christograms, 10th to 12th centuries:

Spanish Chi-Rho (charters) – cursive.

Yes, trust me, they are the same as the Chi-Rho of the Book of Kells, just a little bit evolved.

This cursive form of the Spanish Christogram symbol used in charters, dividing it into three parts (top-middle-bottom) can be read as follows: the vertical stroke is the cursive interpretation of ρ, the kind of loop in the middle is the χ, the dots at the side are punctuation marks, and the stroke at the bottom is the ς that was added around the 10th century corresponding with the usual greco-latin abbreviation XPS in nomina sacra.

As wild and strange as these forms are, the scribes who wrote them recognised the Chi-Rho and, in fact, regulations as for its use can be seen: depending on the production centre – cathedral, monastic or parish scriptoria –, the design of the sign changes. Thus, analysing several hundreds of charters from early 10th century until the late 12th, that is, the Visigothic script corpus, we can see how it evolves, which is great because it allows us to use it to date and locate charters geographically, placing them in their historical/cultural context (this is why I decided to write an article on the sign).

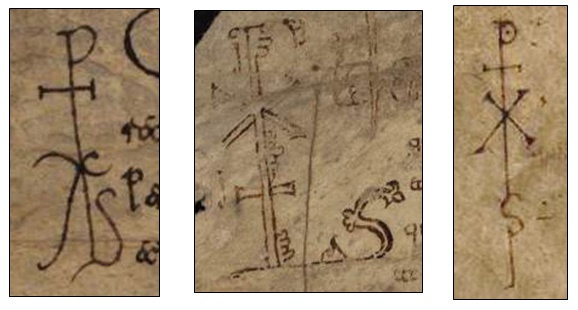

But, there is more. At the same time that this crazy cursive form was used, other scribes decided to use a more ‘classical’ design:

Spanish Chi-Rho (charters) – non-cursive.

Why? As far as I know, it seems that the use of one design or another depends on the cultural relevance of the production centre and on to what extent it was open to external influences or not. It does not depend on the training of the scribe: there were professional scribes using the cursive form, although it is true that parish ones used even more cursive or degenerated forms.

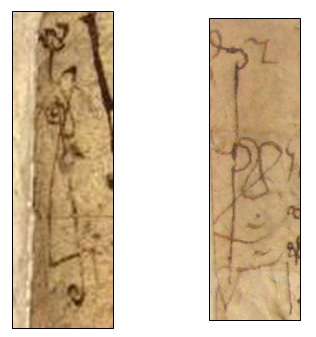

Spanish Chi-Rho (charters) – too cursive!

With regard to how open each centre was and the reception of exogenous influences, another thing worth mentioning is that when Caroline minuscule script arrived, the Chi-Rho also changed. In the first ten examples written in this supranational script, cursive designs of the Christogram can still be found, but in the ones immediately following it is like the sign was turned back to its origins. Why?

Caroline minuscule script Chi-Rho (charters).

So, something I expected to be very methodological, very “palaeographical”, has become an open door to the study of written culture from a much broader historical and social perspective than I anticipated. Now I need to find out why the cursive sign evolved regulated enough as to distinguish various types, as I have done according to the timeline, to analyse the cultural level of each center within Galicia and to study the routes of cultural exchange with the rest of Spain and Europe. It looked as though it was over and it turned out to be only the beginning!

[1] The article was published as A. Castro Correa, “Observaciones acerca de los crismones empleados en la documentación medieval de la diócesis de Lugo (siglos X-XII)”, Scriptorium 69/2 (2015): 3-31.

by A. Castro

[edited 11/07/2018]

Joan Vilaseca

Could you indicate the date and documents with those first ‘carolingian’ chi-ro?

Ainoa

Hola Joan,

Son los siguientes:

AHN1325D/21 (año 1161), AHN1325F/5 (año 1172), AHN1325F/16 (año 1174)

:)

Joan Vilaseca

Gràcies!