Codex of the month (II): British Library, Add. Ms. 11695 (1) The ‘Beatos’

London, British Library, Additional Ms. 11695 > Beatus of Liébana, Commentary on the Apocalypse > dated late 11th-early 12th c. (1091-1109) with Antiphonarium dated 10th-11th c.

* This post has two parts:

(1) The ‘Beatos’ as an introduction to the genre, and

(2) The Codex, with the description of the manuscript British Library 11695 [click here] *

The MS. 11695 kept at the British Library and so-called Silos Apocalypse belongs to one of the most authentic manuscript traditions of the medieval Iberian Peninsula. It is one exemplar of the 32 preserved, copied from the late 8th to the 14th century, widely known as “Beatos”. Each one of these Beatos transmits a thorough, passionate and lavishly illuminated commentary on the Apocalypse of St John of Patmos as well as other texts like the treatise De adfinitatibus et gradibus (a chapter from St Isidore’s Etymologies) and the Commentary on Daniel by Jerome, that were added to the volume as early as the 10th century.

Beato de Liébana

The name “Beatos” used to refer to all these codices comes from the supposed [1] author of the first exemplar, Beato de Liébana, a monk from the southern Iberian Peninsula who settled in the sheltered mountains of Cantabria, in the north, after the Muslim arrival. Both Beato, the monk, and the Beatos, the codices, have been extensively discussed from a wide variety of disciplines, from neurology to art history, besides palaeography or codicography, reaching each scholar very different while erudite conclusions.

The easiest approach to author and work would be that Beatus, the monk, frightened by the upcoming Apocalypse that should have happened in the year 800 but solaced by his profound religiosity, decided to compile all the previous works on the topic he knew about –like those of Ticonio, Abringio or Primasio–, in a unique volume to feel more at ease. But then again, as usually happens, that is not all the truth behind the Beatos and Beato. To begin with, Beato was not only a regular although well-read monk living in Liébana, but one of the most influential intellectuals of early medieval Iberian Peninsula, connected to his cultural past as well as with his coeval most selected colleagues. The task Beato did in the convulse period he lived in was not only contemplative but energetic; he was one of the two parts involved fighting against the Adoptionism quarrel, right alongside Alcuin and Charlemagne [you can read more about this here]. Irate letters to the Toletan archbishop Elipando condensed in his Apologeticum or Adversum Elipandum libri duo make his social status palpable and give a deeper approach to his summa or exegetical treatise. Nonetheless, the Beatus, his Commentary on the Apocalypse, was a result of the monk’s agitated religious context, a summary of medieval doctrine and theological symbolism and a good example of the methods of education of that time. In my opinion, the Beatos are in fact an open window to the 8th century Iberian Peninsula regardless of the perspective from which one wants to address them.

The context

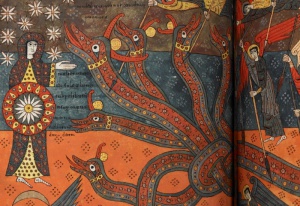

© The British Library, Add. mss. 11695, f.136v The bringers of death with the dead below.

First of all, Beato’s urge for working on the Apocalypse was not (only) a product of his piety, but of his time. The IV Council of Toledo (633) required the continuous reading and explanation of the Apocalypse from Easter to Pentecost under penalty of excommunication. Thus, it can be understood that the provision favoured the extensive use of the Beatos within the Hispanic liturgy, helping to make these codices well known and highly appreciated as works of a special eschatological spirituality. Besides that, the Adoptionism heresy against which Beatus fought is also represented in his Beatus, being the Antichrist identified with those false prophets, meaning Elipando and his followers, who turned away from the true doctrine of Christianity. Even for those not so concerned about these heretics (if that was possible) the Muslims were a good opponent. And, of course, there was the date, 800, and the supposed end of the world by that year according to the calculations of the Christian tradition (6000 years after Adam and Eve).

© The British Library, Add. mss. 11695, f.18v Christ giving a book to an angel; below, the angel giving the book and speaking to St. John.

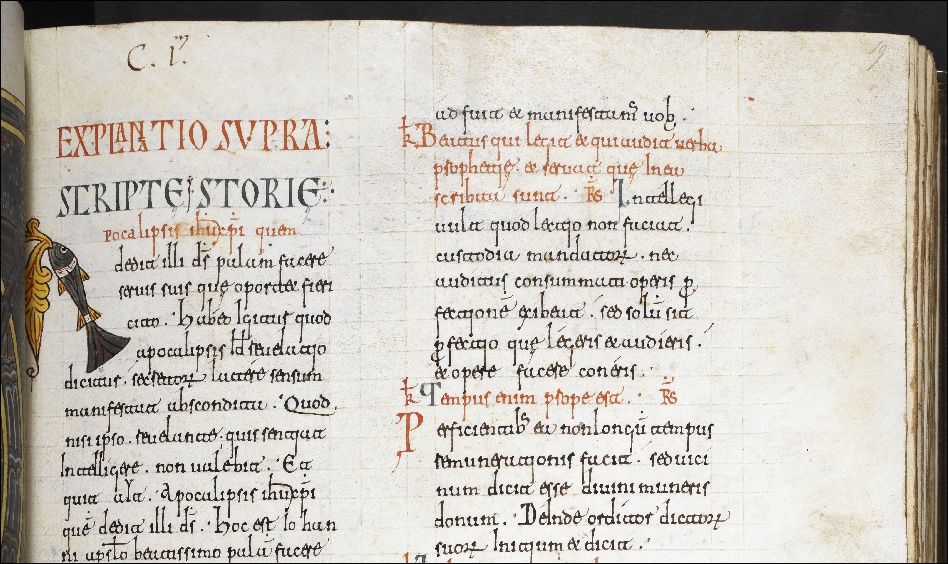

The perfect fit between the Beatus’ content and the religious and historical context was not the only reason for its success. Although the Beatos were considered spiritual books and not purely liturgical ones as the Psalter, the Liber Ordinum, Antiphonaries, Comicus and Manuals, they surpassed their initial purpose and were used for practical and transcendent purposes alike. As the Bible, being books intended to promote a higher intellectual religious discussion among cultured Benedictine monks, they were considered sacred and as such treasures of knowledge. But they were not as the regular spiritual books. The importance of the message transmitted within their context favoured the development of a symbolic language profusely illustrated in the Beatos’ program of illuminations. The concept of the book as a receptacle of knowledge, transmitted from God to men through the angels, is extensively present in this type of books. And there is much more behind the Beatos; not only is the symbolism important but how it was conveyed.

The Beatos

© The British Library, Add. mss. 11695, f.15v Explanatio supra scripte storie.

© The British Library, Add. mss. 11695, f.15v Explanatio supra scripte storie.

Books as the Beatos, given their message, were intended not only to be read, seen and admired, but to be memorised by heart as it happened with the more valuable texts. For that purpose, the work was conceived as a compendium of exegetical knowledge; a unique volume in which everything that needed to be kept in memory was easily exposed and organised.

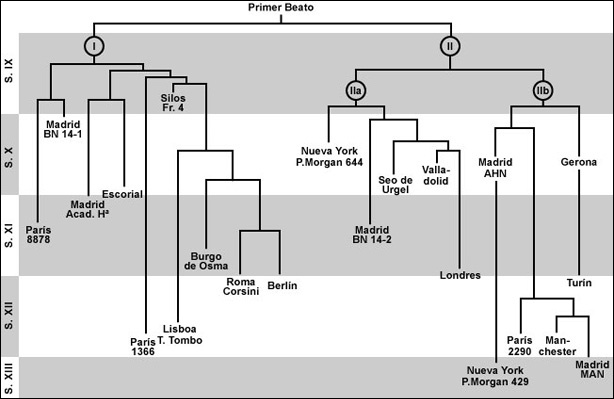

The book was thus conscientiously and thoughtfully divided, after prologue (1) and preface (2), in 12 sections known as storiae (3). These storiae were the text of St John; narrations of events intended to make their literal meaning understood opening the path to their figuratively and mystical full comprehension. The explanatio (4) of each storia, Beatus’ comments, follows, allowing the threefold inmost meditation of each passage with the helpful program of illuminations. Images that stay in memory, can be easily remembered and sumptuously complement the text [see a collection of images here]. To these four basic parts other elements were added depending on the tradition followed in the copy (Beato did several revisions of his text – at least two in 776 and 786) and the context; biblical genealogies, explicit with the definition of terms as codex, liber, volume…, the treatise De adfinitatibus and the Commentary on Daniel by Jerome. As can be seen in the picture below, three families have been distinguished (being the BL 11695 from the family IIa).

Beatos’ stemma.

The world did not end in the year 800 as did not the appreciation for the Beatos. They were not only books for preparing a Christian soul for the Apocalypse but intended for the transcendental comprehension of medieval Christian thought. Being the first exemplar written around the 800, they continued to be best-sellers throughout the Middle Ages, and even today, greatly esteemed for their doctrinal contents and impressive artistic value. Reading or looking at their pages it is impossible not to react, not to think about the medieval peasants, monks, erudites and kings that stared at a Beatus finding a place in their spiritual and physical world.

[1] There is no direct reference to the author of the Beatos in any of the codices or in other texts, although it is accepted that he could have been Beato de Liébana since this work perfectly fits with what is known about his life and his other works.

>>> Read the 2nd part of this post, The Codex, with the description of the manuscript British Library 11695 <<<

by A. Castro

[edited 12/07/2018]

[update July 2017: I have an article in press about this codex. If you are interested please take a look for I no longer agree with some of the things stated in this two posts. Thank you! A. Castro Correa, “The scribes of the Silos Apocalypse (British Library Add. ms. 11695) and the scriptorium of Silos in the late eleventh century”, Speculum (2018, in press)]