How did scribes perceive the graphic change?

To what extent were the scribes aware of the graphic differences between writing systems?

If you are reading this post, you more likely come from its first part “Visigothic script at the 19th Colloquium of the CIPL”. If not, some context: Earlier this month, I gave a paper at the 19th Colloquium of the Comité international de paléographie latine about the change from Visigothic script to Caroline minuscule. There, instead of going through a detailed list of graphic changes, what I did was to organise my presentation into four main unsolved questions which can be extrapolated to any period of graphic change aiming to foster discussion on the topic.

How did scribes perceive the graphic change from Visigothic script to Caroline minuscule? :

- To what extent were the scribes aware of the graphic differences between writing systems?

- Were early 12th-century Galician scribes polygraphic amanuenses?

- How were scribes trained in the new script? Who taught them?

- Was the social status of Visigothic and Carolingian script scribes the same?

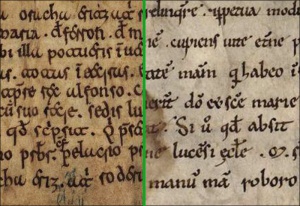

FIG. 1. A glimpse of one of the earliest charters written in Caroline minuscule from Galicia (dated 1126).

FIG. 1. A glimpse of one of the earliest charters written in Caroline minuscule from Galicia (dated 1126).

Medieval scribes did not have the freedom to choose the form of the letters they were using to write as we have now. Rather, they had a model, a standard that was followed by a given geographical area, which usually corresponds to a political entity – meaning a country or group of kingdoms with a cultural link.

As for Visigothic script, as I guess as for many other medieval and modern scripts, it was not decided per se that everything needed to be written in Visigothic; the script just evolved developing to what we identify now as that particular graphic model. Caroline minuscule, on the other hand, was, in the Iberian Peninsula, imposed. From the late 9th century on, the writing system that is Carolingian was spread and prioritised instead of the Visigothic one in the scriptoria that populated the different kingdoms of medieval Spain. Scribes who were, until that moment, using Visigothic, needed, thereafter, to learn and apply Caroline minuscule. Some agree, some others did not.

Such a process of graphic change here roughly explained, offers an exceptional milieu upon which to study many different aspects and not just the scripts used. For example, those scribes who decided not to use Caroline minuscule, even when they were supposed to do so, show objection for a reason, be it respect for a prior cultural tradition for them worth preserving or just old age and reluctance to learn something new. They could belong to a scriptorium that was opposed to all Carolingian graphic, religious, and/or political influence, or they might just have had problems to find and/or afford a master of Caroline minuscule to teach them. As can be seen, the approach accepts a rainbow of possibilities, as many as you want.

FIG. 2. The Harley Psalter, 1st half of the 11th c. © British Library, digitised.

FIG. 2. The Harley Psalter, 1st half of the 11th c. © British Library, digitised.

Regardless of how we want to interpret the graphic change, what is beyond question is that scribes were aware of it. They indeed perceived it. Let us leave aside the historical, political, cultural, and/or religious change to focus upon the graphic one. To what extent were the scribes aware of the graphic differences between writing systems? What my research has shown is that Visigothic script scribes did recognise Caroline minuscule, being aware of its peculiarities.

In comparison with Visigothic, Caroline minuscule has a different set of letterforms – particularly for a, g, I, and t –, and abbreviations – new to the system were, for example, those of noster/uester with theme in r instead of in s [you can read more about abbreviations and letterforms here and here]. Punctuation also has its nuances [more here]. The ductus is, however, not far from that of Visigothic minuscule. Anyway, there was a difference. So, what some Visigothic script scribes did was to start incorporating some of these new features into their hands, using a typology that we now describe as transitional Visigothic script [more here and here].

Did they do it consciously or not? It can only be guessed; say they did. Why? Were they learning the new system and, thus, did not master it yet? Were they trying to add some traces of trendiness even when they did not want to change? Again, those who did not add the new features, why did they preserve the Visigothic model? It is difficult to assess. What it can be said is that, through the close examination of extant charters, they seem to have been a bit confused at first about which features belong to which graphic model, since we find some hands that mixed scripts in a very particular way. See the image below; this is a Visigothic minuscule hand who wrote a Caroline minuscule abbreviation adding also the Visigothic one.

FIG. 3. Caroline minuscule nb + Visigothic script sign for -is © Santiago de Compostela, AHUS., Blanco Cicerón, 188 (dated 1122).

Does this mean that the scribes who mixed both scripts were polygraphic amanuenses, meaning that they were able to write in both scripts, Visigothic and Caroline? I do not think so. Some of them might have been, but not all. In my point of view, most of the scribes working on this transitional period of graphic change were either learning Caroline minuscule or irremediable influenced by it, consciously or not. Another question to ask is whether they were polygraphic Visigothic script scribes; I have already written about this here.

FIG. 4. Codex Vigilanus seu Albeldensis, late 10th c. © El Escorial d.I.2.

FIG. 4. Codex Vigilanus seu Albeldensis, late 10th c. © El Escorial d.I.2.

How was the process of learning a new script for the scribes who decided to change? Leaving aside the dissimilarities between the two writing systems, Visigothic and Caroline do not look so different. Our brain needs to be reminded, though, that in medieval times written culture was not as today. Most of the population now is able to write, in the Middle Ages this was not the case. Thus, to learn a new script must have been a great deal. It is known that Caroline minuscule masters came to the Iberian Peninsula to teach the new script to those who wanted to learn it, but there is no direct evidence to explain how the process itself was. For those who already knew Visigothic, it must have been easier to learn the new features, or maybe not? If we were now obliged to modify the form of our a or t, how long will take to our brain, eye and hand, to actually change? [see related posts about me learning to write in Visigothic script].

FIG. 5. Learning to write in Visigothic script.

FIG. 5. Learning to write in Visigothic script.

Another difference between now and 12th-century Iberian Peninsula is that, back then, writing was a laborious and slow process; it can be assumed their brain had enough time to realise the model the scribe’s hand should follow, or not? This could be another post. Let us just note here that examples of codices in which the copyist lost his thought and wrote some lines in another script have been preserved.

Finally, as for the last question, it has been suggested that those scribes and scriptoria that changed to Caroline minuscule were thus accepting and acknowledging Carolingian cultural pre-eminence. If so, it can be discussed whether Caroline minuscule scribes held a higher status than Visigothic script scribes. In my opinion, to assess this question is tricky if not impossible. I guess that if a centre felt powerful enough to fight for the preservation of its own culture, it did not subdue; while if it was a minor centre it could have done so? What do you think?

PD. If you know about publications tackling one or several of these questions, I would be grateful if you could please let me know.

by A. Castro

[update January 2016: this research will be published in A. Castro Correa, “The regional study of Visigothic script: Visigothic script vs. Caroline minuscule in Galicia”, in ‘Change‘ in medieval and Renaissance scripts and manuscripts: proceedings of the 19th Colloquium of the Comité international de paléographie latine (Berlin, September 16-18, 2015), Turnhout (in press)]

[edited 13/07/2018]