ViGOTHIC update: Making a medieval codex (I)

How was the process of copying the codex British Library Add. mss. 11695, the Beatus of Silos?

During the last few weeks, I have been trying to figure out how the many people who were involved in producing the exemplar of Beatus kept at the British Library worked together; who made what and how they interacted. As a palaeographer, at first, I was mostly concerned with the identification and description of the graphic specifics of each one of the scribes who, as copyists, made the text as is now displayed. But, once I had the hands individualised, since they are remarkably intertwined throughout the quires, I soon realised how the whole process of making the codex was much more complex than expected. There are not only five hands which, in a very short period of time, collaborated in copying the main text contained in the Beatus, the Commentary on the Apocalypse per se, plus the additional texts as the excerpts of the Etymologiae, Jerome’s Commentary on Daniel, and other miscellaneous texts – which, by the way, I am having difficulties to find edited or at least correctly attributed to -, but also different authors for the miniatures who made the illumination programme for which the codex is so worldwide famous. It is obvious that there is much more to a codex than the scribes, but it is somehow easy to forget how not only time-consuming but expensive to make a codex like this one must have been; surely a remarkable event for the scriptorium that speaks of its own conception, means, and managerial skills. Moreover if we bear in mind, following the current state of the art, that this codex, the Silos Beatus, was one of the first ever made at the monastery of Silos.

As many of you may know, revising all the relevant bibliographic references, the palaeographical and codicological analysis of this British Library codex, is the objective of the first part of the project in which I am working now, ViGOTHIC. Having the graphic analysis done, the clues found in defining the collaboration among scribes made me expand the project to incorporate also a revision on the illumination programme, the style and its authors. All this research will be made into an article I expect to finish soon. Meanwhile, I thought about writing here how I picture, at this stage of the project, the whole process of making this medieval codex was.

*

Making a medieval codex (I)

It must have been around the year 1090 when abbot Fortunius, who had been abbot of the Benedictine monastery of Silos (in what is now Burgos) for some twenty years at that time, considered for his monastery to have the resources enough to make a copy of one of the most significant bestsellers of medieval Iberia, a Beatus. Silos was still a very recently revived cenobium, founded around the mid-10thcentury but in decadence as a consequence of the Muslim razzias around the northern Meseta. Fortunius’s Silos was, however, powerful enough thanks to the reorganisation his predecessor, abbot Domingo, had undertaken commissioned by king Fernando I. Domingo was called into to restore the ecclesiastical community living at Silos from the nearby monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla, in La Rioja, and although Cogolla’s monastery and, particularly, its written production was still of higher quality than that of Silos, Domingo’s dedication proved extraordinary. He was canonised as saint soon after his death in 1073. When Fortunius took his place, he not only knew how to maintain Domingo’s will but continued to improve Silos’s well-being making the most of his predecessor’s fame. When Fortunius undertook the task of for his monastery and newly created scriptorium producing a codex, it was a Beatus (The Silos Beatus, BL Add. mss. 11695). But, how was the process?

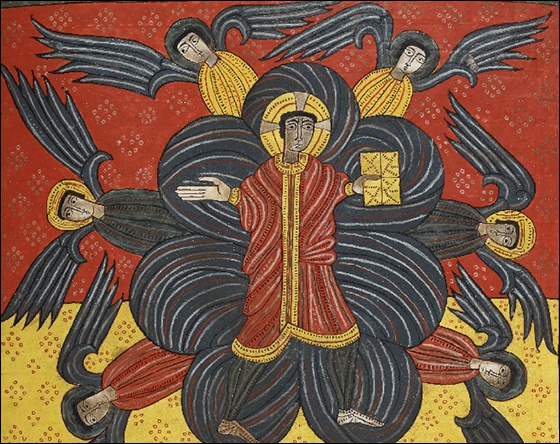

The Silos Apocalypse. © London, British Library, Add. mss. 11695, f. 21 Appearance of Christ in a cloud

The first step the Silos’s scriptorium needed to accomplish to make the codex possible was to gather parchment enough for the work that was to be copied. Bearing in mind the actual measures of a page of the Silos’s Beatus, 380 x 240 mm, and the length of the volume, some 270 folios, this meant to buy or at least to use some of the monastery’s livestock for the purpose of providing the basic raw material for making the codex. Giving the quality of the parchment, quite pale and thin, it must have been, more likely, from calves. If we consider that one calf could have provided at least 2 bifolia, folded twice (quarto) with the measurements of the Beatus, that makes 8 folios of parchment and thus around 34 calves. But first, they needed to make parchment out of the skins.

© Staatsbibliothek Bamberg, msc. Patr. 5, fol. 1v. 12th c.

To produce parchment was a very tedious and cumbersome process that required a specialist (see this short video). The animal skin had first to be removed from the slaughtered animal. The hair then had to be removed as well from that skin by soaking it in a lime bath. After that, the hair and remaining flesh would have been scraped off using a curved knife, sometimes referred to as a “lunellum” for its crescent shape using the Latin word for moon. Once that had been done, the surface had to be treated further so that it would hold ink and pigment painting, and this involved polishing the surface with a pumice stone occasionally applying a very thin layer of chalk.

Parchment was not the only basic material required, especially for a codex like this one with such an intricate illumination programme. The scriptorium needed ink – and quills to apply it! Monks were required to manufacture all the pigments the work they aimed to copy demanded. Ink for the text, carbon ink, and ink for drawing. Many different colours were used for the illuminations; besides different tones of red and a bright yellow, the Silos Beatus displays a special, for its uniqueness, range of dark blue and green inks. A specific analysis of the components of each of the inks used in this manuscript would be of great interest. In the meantime, I recommended you to take a look at this book (particularly from p. 47 on).

Once the scriptorium had the basic materials required, the work on the manuscript could begin.

>>> continue reading <<<

by A. Castro

[edited 13/07/2018]